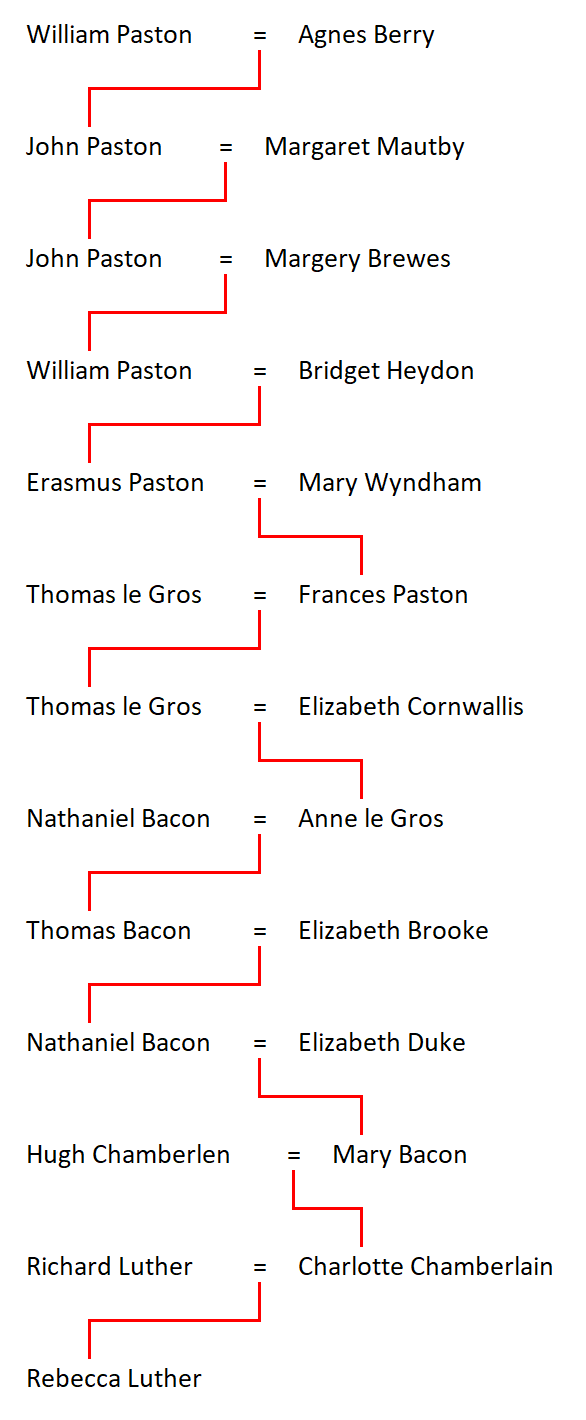

The Pastons of Norfolk

The Paston family were a prominent Norfolk family during the Wars of the Roses. The collection of letters1 that has survived is a primary source for information about life during that turbulent time as experienced by a newly prosperous ambitious family. The letters focus on 3 generations of the Paston family and their disputes with other ambitious newly prosperous families in Norfolk and the Earls of Norfolk and Suffolk.

Interestingly the letters are also a great source of information for linguistic experts as they track the change of colloquial speech from Late Middle English2 to Early Modern English3.

Helen Castor a well-known historian and TV presenter has written an excellent book on the letters called “Blood and Roses” (see Castor (2004)). I would highly recommend this book for anybody who would like to go into more detail on this period of history, and a lot of this section is taken from her book.

The Paston family takes its name from the Norfolk village of Paston4, they would probably have been known using the french “de Paston”.

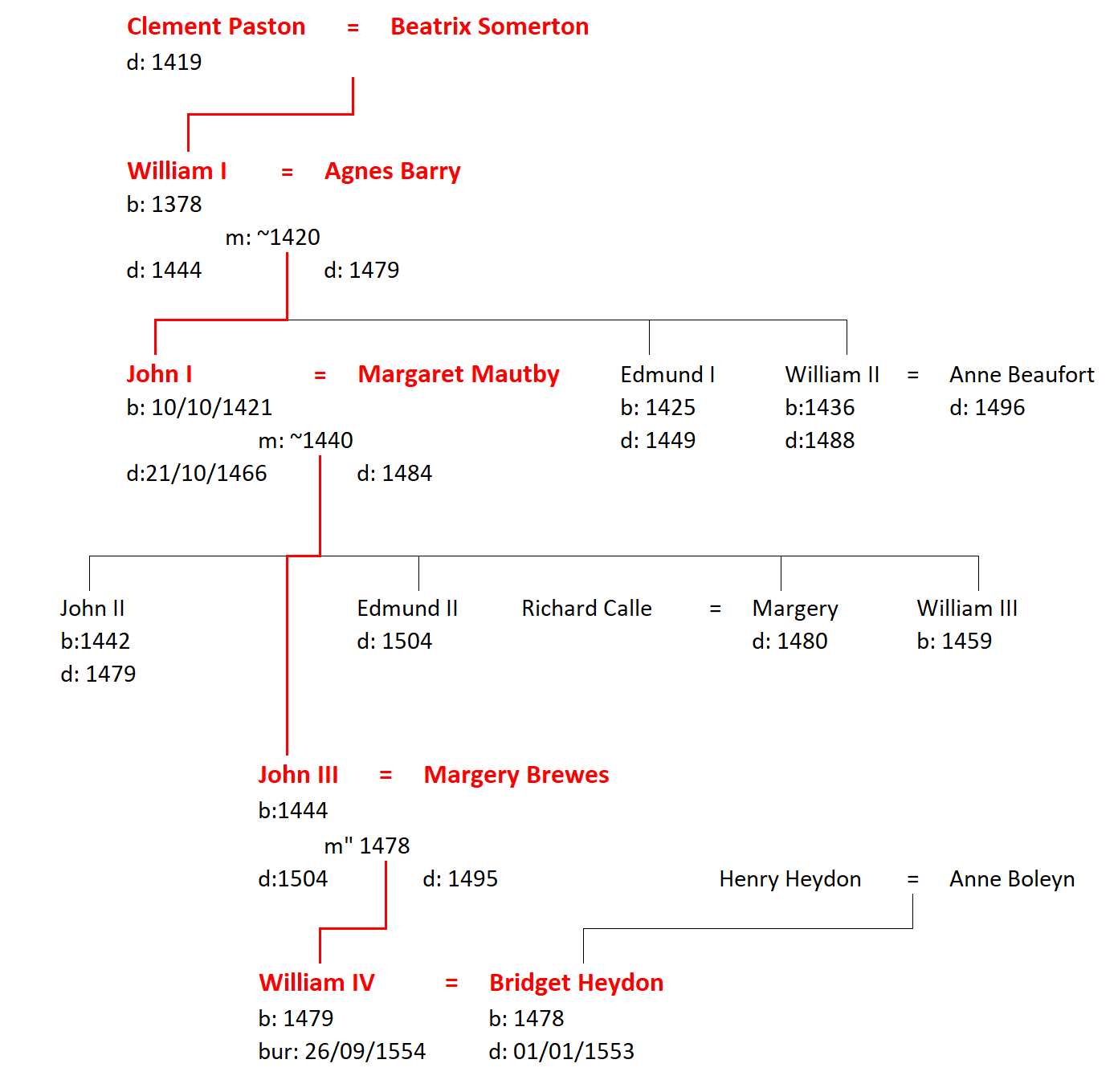

The first known reference to a Paston family is to Clement Paston. He was a yeoman holding and cultivating about 100 acres of land. He married Beatrice Somerton. Her brother Geoffrey became a lawyer and it was due to his generosity that the Paston family began its rise up the social ladder.

Education was the key to social mobility, and there are a few notable examples of how education helped ordinary people rise up the social ladder. William de la Pole was an ordinary merchant in Hull during the mid-14th century, and by the end of the century his son had been knighted and created Earl of Suffolk. Simon Langham grew up in a small village in Rutland, but by the end of his life he had risen to be Archbishop of Canterbury and cardinal at the papal curia.

William Paston, Justice of the Common Pleas (Born 1378)

17th Great Grandfather – FFFMFFMMMFFMFMFFFFF5

Clement and Beatrice had at least one son, William, born in 1378, and Beatrice’s brother Geoffrey paid for William’s education, at grammar school and at the Inns of Court. William first appears in public record in the accounts of Norwich City for 14126, when he was paid by order of the mayor for his services as counsel.

In 1418 William became a serjeant-at-law, and on 15 October 14297 he was appointed a Justice of the Common Pleas, a position he served in until shortly before his death8.

In 1420, the marriage settlement is dated 24 March9, at the age of 42 William married Agnes Barry or Berry, the daughter and coheir of Sir Edmund Barry, by whom he had 4 sons and one daughter.

During his lifetime William had acquired a significant portfolio of real estate, including Gresham which he purchased in 1426 from Thomas Chaucer, the son of Geoffrey Chaucer, the famous writer of The Canterbury Tales.

William died at London on 13 August 1444 and was buried in the Lady Chapel of Norwich Cathedral. His widow, who was only 20 when they married, survived William by 35 years, but never remarried. she died on 18th August 1479 and was buried at Whitefriars, Norwich.

John Paston I (Born 1421)10

16th Great Grandfather – FFFMFFMMMFFMFMFFFF

William’s eldest son John was born 10th October 1421. John was educated at Trinity Hall11 and Peterhouse12 at the University of Cambridge, and like his father, he became a lawyer. He was admitted to the Inner Temple by 144013

John married Margaret Mautby, some time during the summer of 144014, and succeeded his father when only 22 years of age, in 1444. John and Margaret had seven children 5 sons and two daughters. Confusingly his two eldest sons were given the same first name, John, and are referred to as John II and John III. John II never married so the estates finally passed to John III the second son.

It was during the lifetime of John I that the families troubles began. John I had inherited a considerable estate from his father, including Gresham which at this time was the families principal residence.

Gresham had been purchased by John’s father William from Thomas Chaucer. However, there was some dispute to the ownership of the property with Lord Moleyns who had a potential claim to the property through his wife, and in February 1448 Lord Moleyns asserted his claim to the manor of Gresham, and with a posse of supporters drove him out of the manor. John I eventually regained possession of Gresham in 145115.

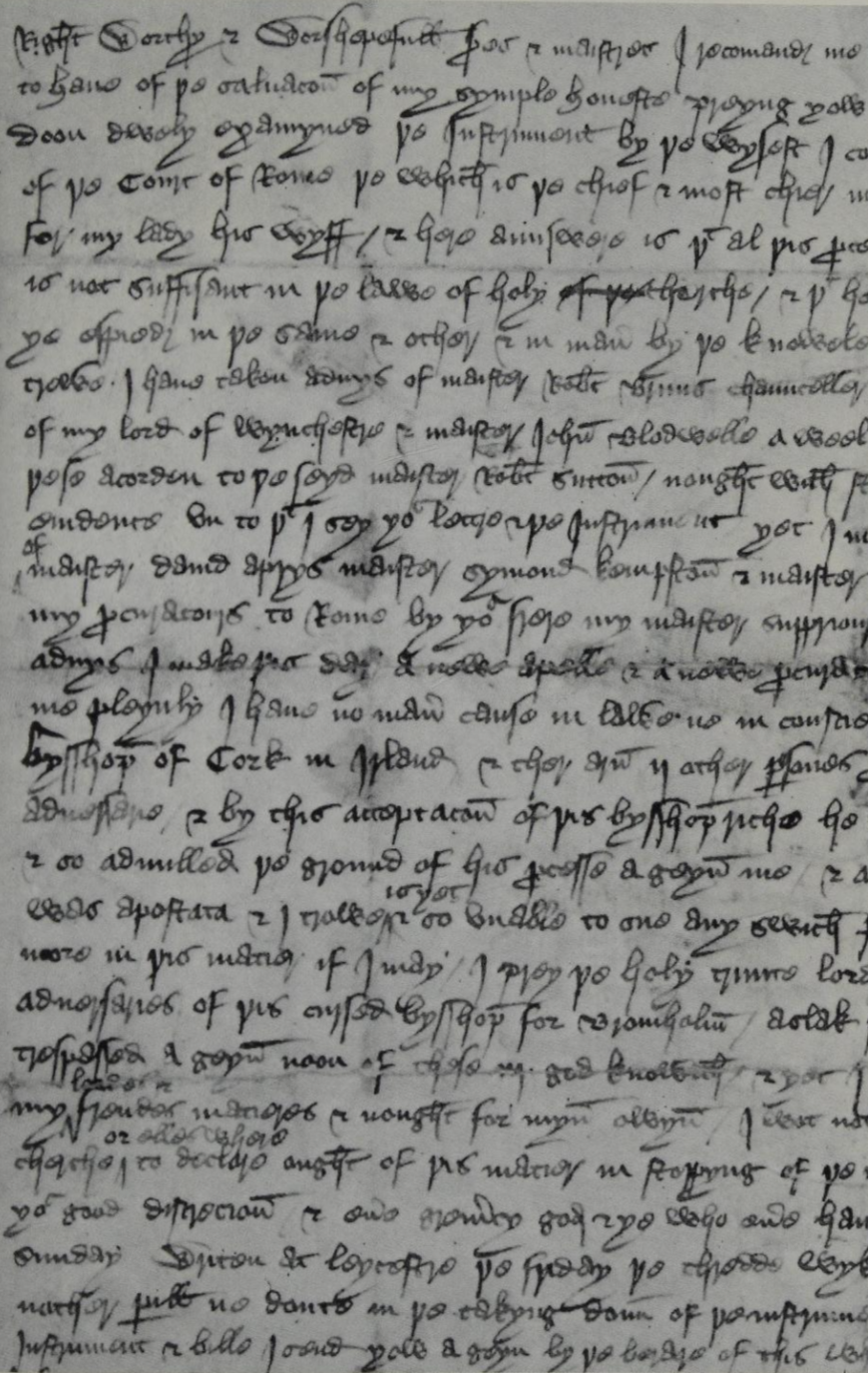

During the 1450s, John became an advisor to Sir John Fastolf, who was related to his wife Margaret16. In 1456 he was appointed one of the feoffees of Fastolf’s lands. In 1459 Fastolf made a will which provided that his ten executors found a college in Caister, Fastolf’s manor. However, after Sir John Fastolf’s death on 5th November 1459, John I claimed that on 3rd November Fastolf had made a nuncupative17 will that gave John I exclusive authority over the establishment of the college, and providing that, after payment of 4000 marks, John I was to have all of Fastolf’s lands in Norfolk and Suffolk.

Relying on this will, John I took immediate possession of the Fastolf estates and resided, at times at Fastolf’s manor at Caister. John I’s claim was immediately challenged by the Duke of Norfolk, who seized Caister in 1461, as well as by others, including the Duke of Suffolk, who claimed two of Sir John Fastolf’s manors in Norfolk.

In 1464 a legal challenge to John I’s executorship was madeby William Yelverton, one of the original 10 executors, but the case had not been resolved at the time of John I’s death and it became a recurring challenge for his sons to make good their father’s claim to inherit the Fastolf estates.

During the 1460s, John I was Justice of the Peace for Norfolk as well as a Member of Parliament for Norfolk18.

During the latter years of his life John I fell out with his eldest son John II, despite his wife Margaret’s attempts at reconciliation, although they did finally reconcile shortly before his death19. John I died in London on May 21st or 22nd 1466 and was buried in Bromholm Priory, Norfolk.

On John I’s death, his estates passed to his eldest son John II. He carried on the legal disputes over the Fastolf estates. Like his father he served as a Member of Parliament for Norfolk20 and a Justice of the Peace for the county. However he really wasn’t temperamentally suited to the dispute, and spent most of his time in London21.

He left his younger brother, John III, and mother in charge of defending the family’s possessions in East Anglia. In 1469, John Mowbray, 4th Duke of Norfolk laid seige to Caister and after 5 weeks John III was forced to surrender, although after the Duke of Norfolk’s death in 1476, the Pastons did finally regain possession of Caister.

John II died in November 1479, when the estates passed to his younger brother John III.

John Paston III

15th Great Grandfather – FFFMFFMMMFFMFMFFF

John III was the second son of John I and Margaret Mautby. Nothing is known about his education, he does not appear to have gone to University like his older brother. The first record of John III is in 1459, when he appears to be acting as his mother’s secretary22.

From 1462 to 1464 he served under the Duke of Norfolk at Newcastle upon Tyne23, and at Holt Castle in Denbighshire24. He went to Bruges with his older brother John II as part of the retinue for King Edward IV’s sister, Princess Margaret’s marriage in July 1468 to the Duke of Burgundy25.

In 1469 he was back at Caister managing the family’s affairs when as mentioned above it was attacked by the Duke of Norfolk’s men. He was able to withstand the siege for a few weeks, but eventually he had to surrender the castle to the Duke.

In April 1471, he was wounded26 while fighting with his elder brother John II and John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford on the losing Lancastrian side at the Battle of Barnet27 He was pardoned the following July.

John III married Margery Brewes in 147728. They had 2 sons and 1 daughter. The oldest son Christopher died sometime before 1482.

In 1479 John’s older brother John II died and John III inherited the estates, although his uncle (William II) initially obstructed his claim.

John III’s lot improved somewhat under the Tudors, he was Member of Parliament for Norwich in 148529 and Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk. He fought for the King at the battle of Stoke on 16 June 148730, and he was knighted on the field by the King31.

John’s wife Margery died in 1495 and was buried at Whitefriars church in Norwich. John remarried Agnes the twice-widowed daughter of Nicholas Morley. It is not known whether they had any children or not. John III died on 28th August 1504, when the estates passed to his surviving son William IV.

William Paston IV

15th Great Grandfather – FFFMFFMMMFFMFMFF

William Paston was born in 1479. There is much less information about William than his predecessors, as the main letter writers were John I and Margaret and their two sons John II and John III. Not much is known about William’s childhood and there is only one letter written by him in the collection. He mentions in this letter32 to his father John III, that he is in Cambridge, but there is no mention of which college.

William marries Bridget Heydon, daughter of Sir Henry Heydon and Anne Boleyn, great great aunt of the famous “Anne” who married Henry VIII. Sir Henry’s father John had been one of the protagonists against William’s grandfather John I, as one of the principal agents of William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk33.

The marriage had been planned since both of them were children. It was not unusual in those days for parents to negotiate with prospective families for the marriage of their children, especially if there was a hope of making peace34.

William was Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk in 1517-18, was knighted by 1520 and attended at the Field of Cloth and Gold in June 1520, as a representative from Norfolk35.

William and Bridget had at least 4 sons, Erasmus36, John37, Thomas38 and Clement39 and 1 daughter, Eleanor40. While all 4 surviving sons became Members of Parliament, Eleanor was probably the most famous, as she became the Countess of Rutland, by marrying Thomas Manners, who was elevated to the Earldom after their marriage. She was a lady in waiting to 5 of Henry VIII’s wives, from Anne Boleyn to Katherine Parr.

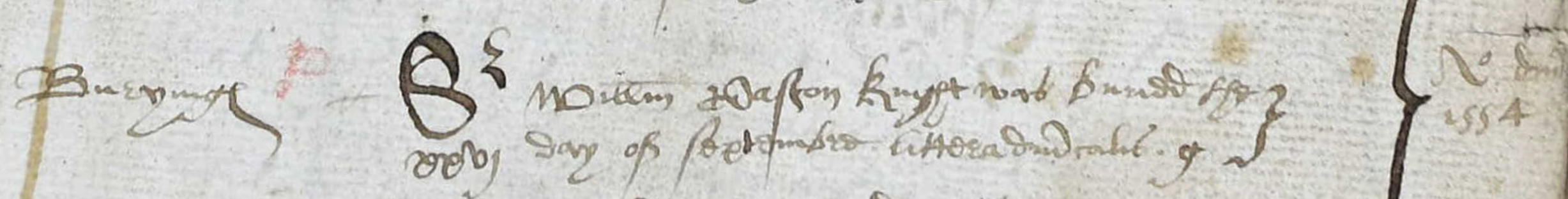

William’s wife Bridget died on New Years Day 1553 and was buried at Paston on 17th January, and William died the following year, being buried at Paston on 26^th September 1554. William had written his will in June, and Probate was given on 4th December 155441. He was succeeded by his grandson, William, the eldest son of his son Erasmus, who had predeceased him by 14 years.

Erasmus Paston

14th Great Grandfather – FFFMFFMMMFFMFMF

Erasmus Paston was the eldest son of William Paston IV and Bridget (nee Heydon). He was born about 1495. It is assumed that he received some kind of education as the eldest son of a well-todo family, but there is no record of him at either of the major universites. He was elected to Parliament for the seat of Orford in Suffolk, and was the only Paston to have sat in a Suffolk seat.

He married Mary Wyndham, daughter of Sir Thomas Wyndham of Felbrigg42. Erasmus and Mary had at least four children, two sons William and Edmund and two daughters, Frances and Gertrude. My ancestor Frances married Thomas le Groos43. They were the 2x great grandparents to Nathaniel Bacon, the Virginia rebel.

References

“Battle of Barnet.” 2025. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Battle_of_Barnet&oldid=1287612278.

“Battle of Stoke Field.” 2025. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Battle_of_Stoke_Field&oldid=1287612358.

Castor, Helen. 2004. Blood and Roses. London: Faber; Faber, Ltd.

Davis, Norman. 2004a. Paston Letters and Papers of the Fifteenth Century. Vol. 1. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. https://archive.org/details/pastonletterspap0000unse/mode/1up.

———. 2004b. Paston Letters and Papers of the Fifteenth Century. Vol. 2. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. https://archive.org/details/pastonletterspap0000unse_k1r9/mode/1up.

“Early Modern English.” 2025. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Early_Modern_English&oldid=1292294909.

“Eleanor Manners, Countess of Rutland.” 2025. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Eleanor_Manners,_Countess_of_Rutland&oldid=1272962029.

“England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858.” 2013. Ancestry.com. 2013. https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/5111/.

“Field of the Cloth of Gold.” 2025. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Field_of_the_Cloth_of_Gold&oldid=1289767492.

Hudson, Rev. William, and John Cottingham Tingey, eds. 1910. The Records of the City of Norwich. London: Jarrold; Sons Ltd. https://archive.org/details/recordsofcityofn02norwuoft/mode/1up.

“John Fastolf.” 2025. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=John_Fastolf&oldid=1291250044.

“John Paston (Died 1479).” 2025. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=John_Paston_(died_1479)&oldid=1288964015.

“Justice of the Common Pleas.” 2024. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Justice_of_the_Common_Pleas&oldid=1292207643.

“Middle English.” 2025. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Middle_English&oldid=1288871804.

“Oral Will.” 2024. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Oral_will&oldid=1241293108.

“Paston.” 2025. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Paston,_Norfolk&oldid=1276261380.

“PASTON, Clement (by 1523-98), of Oxnead, Norf.” 1964-2020. The History of Parliament Trust. 1964-2020. https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1558-1603/member/paston-clement-1523-98.

“PASTON, Erasmus (by 1508-40).” 1964-2020. The History of Parliament Trust. 1964-2020. http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1509-1558/member/paston-erasmus-1508-40.

“PASTON, John (1510/12-75/76), of Paston, Norf. And Huntingfield, Suff.” 1964-2020. The History of Parliament Trust. 1964-2020. https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1509-1558/member/paston-john-151012-7576.

“Paston Letters.” 2025. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Paston_Letters&oldid=1291969210.

“PASTON, Sir Thomas (by 1517-50), of London.” 1964-2020. The History of Parliament Trust. 1964-2020. https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1509-1558/member/paston-sir-thomas-1517-50.

Rye, Walter, ed. 1891. The Visitation of Norfolk, 1563, 1613. London: The Harleian Society. https://archive.org/details/visitacionievisi32ryew/mode/1up.

Shaw, WM. A. 1906. The Knights of England. Vol. 2. London: Sherratt; Hughes. https://archive.org/details/knightsofengland02shawuoft/knightsofengland02shawuoft/page/n10/mode/1up.

Wedgwood, Josiah C. 1936. History of Parliament, Biographies of the the Members of the Commons House, 1439-1509. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office. hhttps://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.210096/page/n5/mode/1up.

Footnotes

-

When showing relationships F means Father, M means Mother, U means Uncle and A means Aunt. So FFM is my father’s father’s mother, and FFMU is my father’s father’s mother’s uncle.↩

-

(Hudson and Tingey 1910), pp. 58-60.↩

-

(Davis 2004a), p. liii.↩

-

see (Davis 2004a), p. lii.↩

-

There are a number of John’s and Williams referenced in the Paston Letters and they are identifed in a standard manner as John I, John II, and William I etc. Thus the earliest “John” is John I.↩

-

A letter from John Gyn is addressed to John at Trinity Hall in Cambridge, see (Davis 2004b), no. 438.↩

-

A letter from John’s wife Margaret to John at Peterhous in Cambridge, thought to have been written soon after they were married see (Davis 2004a) no. 124.↩

-

A letter from John’s wife Margaret to John at the Inner Temple at London, see (Davis 2004a), no. 126.↩

-

A letter written by John’s mother Agnes to his father William on 20th April 1440 is obviously written prior to their marriage, see (Davis 2004a), no.13, while a letter from Robert Repps to John himself, dated on 1 November 1440 shows he was married by then see (Davis 2004b), no. 439.↩

-

Many of the disputes the Pastons were involved in were caused by the ongoing rivalry between John Mowbray, 3rd Duke of Norfolk and William de la Pole Duke of Suffolk, who due to his influence over King Henry VI, attempted to dislodge the Duke of Norfolk from his position as the premier Duke in East Anglia. Suffolk fell from power in 1450 and early in 1451, John I regained possession of the manor of Gresham.↩

-

Sir John Fastolf was a wealthy military man and is thought to have been the prototype for Shakespeare’s Falstaff in his Henry IV and V plays, see (“John Fastolf” 2025) .↩

-

A nuncupative will is a will that had been delivered orally, see (“Oral Will” 2024).↩

-

see (Wedgwood 1936), pp. 665-666.↩

-

see (Wedgwood 1936), pp. 665-666.↩

-

see (Wedgwood 1936), pp. 665-666.↩

-

see (Davis 2004a), no. 152, 154, 155, 157, 163-5, 167-70.↩

-

On 11 December 1462 John III wrote a letter to his brother John III from Newcastle with news of the fighting in the North between Warwick and margaret of Anjou’s forces, see (Davis 2004a), no. 320.↩

-

On 1 March 1464 John III wrote a letter to his father John I from Holt Castle, see (Davis 2004a), no. 321.↩

-

On 8 July 1468 John III wrote a letter to his mother Margaret from Bruges, describing some of the goings on at the wedding, see (Davis 2004a), no. 330.↩

-

John III’s brother John II describes his injury in a letter to their mother four days after the Battle, letting her know that they are both alive and well except for John III’s minor arrow wound see (Davis 2004a), no. 261.↩

-

see (“Battle of Barnet” 2025)↩

-

see (Davis 2004a), no. 226, 374-9.↩

-

see (Wedgwood 1936), p. 665.↩

-

see (Davis 2004a), no. 421.↩

-

William’s uncle Edmund Paston II mentions the marriage in a letter to William’s father sometime between June 1487 (when William would have been 7 or 8) and February 1493 (when William would have been about 13) see (Davis 2004a), no. 400.↩

-

William’s uncle Edmund Paston II mentions the marriage in a letter to William’s father sometime between June 1487 (when William would have been 7 or 8) and February 1493 (when William would have been about 13) see (Davis 2004a), no. 400.↩

-

see (“PASTON, John (1510/12-75/76), of Paston, Norf. And Huntingfield, Suff.” 1964-2020).↩

-

see (“PASTON, Sir Thomas (by 1517-50), of London.” 1964-2020).↩

-

see (“PASTON, Clement (by 1523-98), of Oxnead, Norf.” 1964-2020).↩

-

The Will of William Paston, dated 20 Jun 1554, see (“England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858” 2013), PROB 11/37/11.↩